About Clarksville

Evelyn Scott (1893-1963)

Regional Connection: Born Elsie Dunn in the Thomas Mansion at 611 Madison (later became Gracey Mansion). Moved with her parents to a small house near the train depot. Mother’s family, the Thomas’s, first settled on a plantation near Clarksville, then became Clarksville businessmen and professionals. Father’s family was from North and involved with the railroad. Elsie Dunn moved frequently as a child but always spent months of each year in Clarksville until she was sixteen.

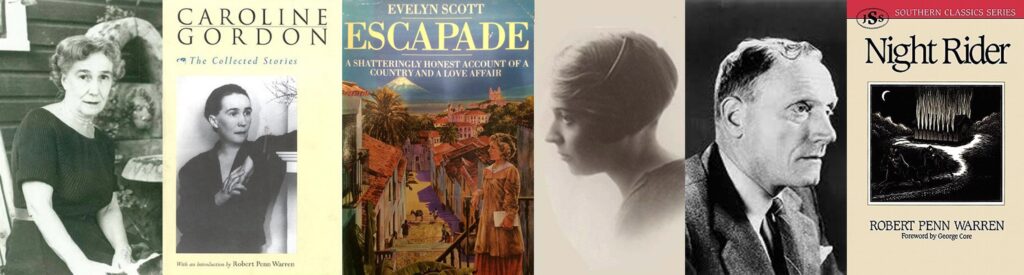

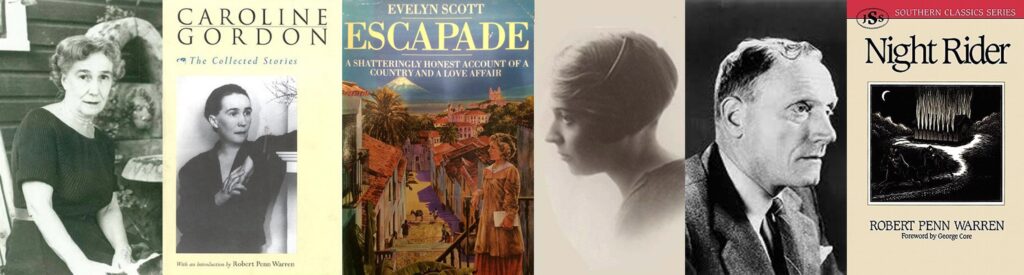

Caroline Gordon (1895-1981)

Regional Connection: Born on her grandmother’s farm on the Kentucky border near Northeast High School. Her mother’s family, the Meriwethers, had a network of plantations running along the border beginning around 1800. Her father came from Virginia to teach the Meriwether children. Moved several times with her father’s teaching and preaching positions. In her teens, lived and was one of her father’s students in his school on Madison Street (near old Clarksville High School). Later taught at Clarksville High School. Returned with her husband, writer Allen Tate, in the 1930s and lived at Benfolly, along the Cumberland River.

Robert Penn Warren (1905-1989)

Regional Connection: Father working as a clerk in the John McGehee country store in Clarksville when he met RPW’s mother, Anna Ruth Penn, who was living on her grandfather’s farm in Cerulean. When McGehee opened his store in Guthrie, RPW’s moved to Guthrie and soon after married Anna Ruth and became clerk and cashier at Farmers and Merchants Bank. RPW was raised in Guthrie until he graduated from high school at age 16 and moved to Clarksville for one more year of high school before beginning at Vanderbilt.

A Rich Literary Tradition

A History

The following essay on Clarksville writers and their relationship to the literature and culture of their time is by Steven Ryan.

Tennessee’s counterforce of modernism is Evelyn Scott, a writer as Dionysion as Ransom is Apollonian. While Ransom remained within a supportive literary community that nurtured his reputation as he nurtured the reputations of so many others, Scott isolated herself in her later years, suffering from paranoid psychosis in a seedy New York hotel. Yet in her youth she had rivaled William Faulkner as the primary modernist voice of the South. Born Elsie Dunn in Clarksville, Tennessee, in 1893, she descended from a northern railroad family and a southern family with aristocratic pretensions. In 1909 she moved with her family to New Orleans and in 1913 ran off with a married man, Frederick Wellman. They took the names Evelyn and Cyril Kay Scott to evade prosecution through the Mann Act and tried homesteading in Brazil. In 1919 the Scotts moved to Greenwich Village where Evelyn became one of the bright young stars of literary bohemianism with her first collection of poems, Precipitation (1920), and her first novel, The Narrow House (1921). Darwinian, Freudian, and Nietzschean, Scott writes about the powers that lie beyond control, beneath consciousness.

The Narrow House focuses on a dysfunctional family that clings together, as intent on self-destruction as on self-preservation. No “clean and formal workmanship” is possible within Scott’s raw, confrontational art. Whatever civility exists within her community must be stripped away to expose the all-consuming powers of appetite and ego. Scott’s best work, Escapade (1923), is an experimental autobiography which captures Scott’s personal hell as she gives birth to her only child in a verdant, infested Eden. Scott writes about pain, physical and psychic, and she offers no assurance that community can offer protection. In 1927 her novel, Migrations, begins her shift from more concentrated, imagistic novels to more historical, southern novels, but her style remains experimental as exemplified by her stunning Civil War novel, The Wave (1929), a novel organized in vignettes similar to John Dos Passos’ Manhattan Transfer (1925). Scott established her reputation before Faulkner and aided him with her introductory essay on the soon-to-be-released The Sound and the Fury. She published a total of nineteen books, but even before her death in 1963, she had been nearly forgotten. Her opposition to the powerful leftist critics of the 1930s led her deeper and deeper into paranoia and oblivion. Although she agreed with the Agrarians that communism was not a viable solution to what ailed America, she was equally critical of what she perceived as the Agrarian tendency to envision a stable antebellum society as a model for a future society. In Background in Tennessee (1937), Scott argues that Tennessee never had time to establish a stable society before the Civil War and considers the southern aristocracy a cultural illusion. Scott looked at the world from T’other Mounting. Like Harris, she cut beneath what she saw as the artifice of culture. She believed in the power of the primeval, and her art would not adapt to cultural traditions and expectations. For Tennessee literature, Scott represents a minority position within the modernist period. With Nashville as its center and Ransom as its master, the Fugitive/Agrarian/New Criticism movements defined the nature of southern life and southern literature. The most accomplished writers of this group were marginal Tennesseans: Allen Tate and Robert Penn Warren, Kentuckians by birth, although both had “border backgrounds” and spent a number of years in Tennessee. Tate was born in 1899 in Winchester, Kentucky, and moved frequently during his childhood, including briefly to Nashville where he later returned to attend Vanderbilt. During the 1930s, he lived with his wife, Caroline Gordon, at Benfolly, their farm outside Clarksville which became a popular outpost of the Nashville-based Agrarians. Tate’s role is central to all three tiers (Fugitive/Agrarian/New Criticism). Among his best poems are “The Mediterranean,” “Aeneas at Washington,” and “Ode to the Confederate Dead.” As a poet Tate is similar to Ransom in that his most admired poems were written in his youth (before 1935), although he, like Ransom, continued to revise his poems through the second half of his life. Tate’s poems tend to be more self-consciously erudite, but, like Ransom’s best work, they are wonderfully controlled meditations that emphasize the degeneration of modern man from a lost heroic tradition. In “Mediterranean,” after imagining Aeneas’ ancient heroic quest, the conquest of the New World is described thus: “We’ve cracked the hemisphere with careless hand!” In “Aeneas at Washington,” the eternal Aeneas begins with his valor in leaving Troy but concludes with his New World vision: “stuck in the wet mire.” And in “Ode to the Confederate Dead” the impotent meditations of the modern man must occur outside the gate of the realm of the heroic Confederate dead. In his late years, Tate devoted more time to criticism and, like Ransom, promoted the literature he admired (Dante near the top of the list, Poe near the bottom), while also developing the New Critical approach to literary study, an approach that encouraged close examination of the text, an appreciation for literary devices and artistically achieved unity, and a respect for tradition without facile, superficial preoccupation with biographical and historical background.

Robert Penn Warren was befriended by Tate soon after Warren arrived at Vanderbilt. Warren, born in Guthrie, Kentucky, in 1905, was only seventeen at the time. As the youngest member of the Fugitive group, Warren quickly established himself as one of the best poets. Yet unlike the careers of Ransom and Tate, Warren is more likely to be remembered for his late-life poetry. Warren might best be seen as the John Dryden of his age. His total impact in literature is difficult to gauge because he is equally accomplished in poetry, fiction, and criticism. Typically, one now finds more emphasis on his poems published after 1950, including his long poems, Brothers to Dragon (1953) and Audubon: A Vision (1969). Some of his best poems were published after Warren’s seventieth birthday: “American Portrait: Old Style,” “Mortal Limit,” and “Doubleness in Time.” These poems drop the classical structure and more austere detachment of the Fugitive period. As a critic, Warren combined with Cleanth Brooks to write the influential New Critical anthologies that shaped America’s literary landscape after World War II. Yet Warren’s intellectual connection with the Fugitive/Agrarian/New Criticism movements was tenuous even in the earlier stages. His contribution to I’ll Take My Stand, “The Briar Patch,” called attention to racial injustice and was considered too progressive by Donald Davidson. In later years, Warren’s views on desegregation moved him yet further from Davidson’s conservative position.

Warren’s fiction typically portrays the Tennessee/Kentucky border area beginning with his first novel, Night Rider (1939), which portrays the area’s Black Patch War between tobacco farmers and tobacco companies. This rural area, as in his short story collection, Circus in the Attic (1948), draws upon the history of his home territory, essentially the triangle from Guthrie and Hopkinsville, Kentucky, to Clarksville, Tennessee. One of his best early novels, Gates of Heaven (1943), and his brilliant last novel, A Place to Come To (1977), use both rural Tennessee and Nashville. The novels are worthy of close comparison as Warren introduces a Dantesque vision of Nashville in both cases. Gates of Heaven investigates how a former college football hero, Jerry Calhoun, is released from his agrarian roots and corrupted by progressivism. The entrepreneur’s daughter, Sue Murdock, is an excellent portrayal of the 1920s new woman who is independent and brazenly aggressive on the surface but beneath the surface has been damaged by a loveless family. A Place to Come To offers a similarly powerful but damaged woman, Rozelle Hardcastle. The protagonist, Jediah Tewkberry, is like Jerry Calhoun in that the story involves his movement from an agrarian background to urbane sophistication. Again, Warren contemplates the dangers of what is lost by disassociation from one’s agrarian roots, but in this case one can see that Warren’s Agrarian principles have faded to the background. The later novel, like Warren’s late poetry, employs a more personal and picaresque approach to experience, one less inclined to read personal history according to the Agrarian paradigm. Warren’s affection for far less disciplined writers, like George Washington Harris and Theodore Dreiser, is apparent, and the treatment of explicitly sexual material is a deliberate affront to conventional good taste. Although Warren has consciously used Dante’s Inferno as inspiration in both texts, in A Place to Come To, he is equally inspired by Yeats’ “Crazy Jane Talks with the Bishop” and has, as in his late poetry, created a more complex tension between art/life as conscious design and art/life as uncontrollable, inexplicable engagement. A Place to Come To deserves to be ranked with Warren’s finest novels, All the King’s Men (1946) and World Enough and Time (1950).

Two accomplished Tennessee fiction writers who are closely connected with Ransom, Tate, and Warren are Andrew Lytle and Caroline Gordon. Both are passionately Agrarian, and both are consummate craftsmen. Lytle was born in Murfreesboro in 1902 and one of his earliest publications is his contribution in I’ll Take My Stand, “The Hind Tit.” He was a teacher of writing through much of his life (U. of Iowa, U. of Florida) and is as well known for his editorship with the Sewanee Review as for his novels; however, his novels are impressive achievements, particularly the short novel, A Name for Evil (1947) and his final, experimental novel, The Velvet Horn (1957). A Name for Evil is a reminder of the profound influence of Henry James on the Agrarian writers. The novel, a psychological gothic thriller much like The Turn of the Screw, is a nightmarish contemplation of the force that land has over humans. The Agrarian concept of the return to the ancestral land is here investigated in terms of the dark stain upon the human that prevents a return to pastoral tranquility. A disturbing illustration of the conservative Agrarian’s difficulty in dealing with race is apparent in Lytle’s early story, “Mr. McGregor.” In this story of an antebellum plantation, the planter kills a slave when the slave attempts to avenge the whipping that Mr. McGregor has given the slave’s wife. Lytle’s focus on the complex dynamics of Mr. and Mrs. McGregor unjustifiably diverts attention from the brutal reality of slavery.

Caroline Gordon, like Lytle, is a conservative Agrarian who is also well known for her teaching as well as her writing. Gordon was born in Todd County, Kentucky, less than a mile from the Tennessee border. As a child she moved to Clarksville where she was educated in her father’s classical school. Gordon was far more prolific than Lytle, publishing nine novels and two collections of short stories before her death in 1981. Like Lytle, Gordon is never lacking in proficiency; she is essentially a writer’s writer. As exemplified by her first novel, Penhally (1931), her fiction often uses her Meriwether relatives who settled along the Kentucky/Tennessee border around 1800. Life in the fictionalized Clarkville is associated with the decay of Agrarian ideals. Her best novel may be Aleck Maury, Sportsman, her collaboration with her father. None Shall Look Back (1937) is often ranked among the best Civil War novels, The Garden of Adonis (1937) is her perceptive Agrarian response to the Depression, and The Women on the Porch (1944), a dark contemplation of love relationships inspired by her tumultuous marriage with Tate, is her most underrated novel. After this novel, Gordon’s fiction is deeply influenced by her conversion to Catholicism. The most successful of the later novels is The Strange Children (1951) which fictionalizes her life at Benfolly during the 1930s. As impressive as Gordon is as a novelist, her greatest accomplishments may be her short stories. Like her novels, her stories are always technically refined (Gordon would become Flannery O’Connor’s technical adviser). Among her best stories are “The Petrified Woman,” “Old Red,” and “The Presence.” An oddity of Tennessee literature is that the small city of Clarksville produced two important writers, Gordon and Scott, at approximately the same time and that these women looked at Tennessee from such sharply contrasting perspectives. Scott is the voice of T’other Mounting, essentially countercultural; Gordon is the voice of Old Rocky-Top, essentially reaffirming the importance of traditional art and culture.

(from The Companion to Southern Literature, Eds. Joseph M. Flora and Lucinda H. Mackethan. LSU, Baton Rouge: 2002.)

About Clarksville

Evelyn Scott (1893-1963)

Regional Connection: Born Elsie Dunn in the Thomas Mansion at 611 Madison (later became Gracey Mansion). Moved with her parents to a small house near the train depot. Mother’s family, the Thomas’s, first settled on a plantation near Clarksville, then became Clarksville businessmen and professionals. Father’s family was from North and involved with the railroad. Elsie Dunn moved frequently as a child but always spent months of each year in Clarksville until she was sixteen.

Caroline Gordon (1895-1981)

Regional Connection: Born on her grandmother’s farm on the Kentucky border near Northeast High School. Her mother’s family, the Meriwethers, had a network of plantations running along the border beginning around 1800. Her father came from Virginia to teach the Meriwether children. Moved several times with her father’s teaching and preaching positions. In her teens, lived and was one of her father’s students in his school on Madison Street (near old Clarksville High School). Later taught at Clarksville High School. Returned with her husband, writer Allen Tate, in the 1930s and lived at Benfolly, along the Cumberland River.

Robert Penn Warren (1905-1989)

Regional Connection: Father working as a clerk in the John McGehee country store in Clarksville when he met RPW’s mother, Anna Ruth Penn, who was living on her grandfather’s farm in Cerulean. When McGehee opened his store in Guthrie, RPW’s moved to Guthrie and soon after married Anna Ruth and became clerk and cashier at Farmers and Merchants Bank. RPW was raised in Guthrie until he graduated from high school at age 16 and moved to Clarksville for one more year of high school before beginning at Vanderbilt.

A Rich Literary Tradition

A History

The following essay on Clarksville writers and their relationship to the literature and culture of their time is by Steven Ryan.

Tennessee’s counterforce of modernism is Evelyn Scott, a writer as Dionysion as Ransom is Apollonian. While Ransom remained within a supportive literary community that nurtured his reputation as he nurtured the reputations of so many others, Scott isolated herself in her later years, suffering from paranoid psychosis in a seedy New York hotel. Yet in her youth she had rivaled William Faulkner as the primary modernist voice of the South. Born Elsie Dunn in Clarksville, Tennessee, in 1893, she descended from a northern railroad family and a southern family with aristocratic pretensions. In 1909 she moved with her family to New Orleans and in 1913 ran off with a married man, Frederick Wellman. They took the names Evelyn and Cyril Kay Scott to evade prosecution through the Mann Act and tried homesteading in Brazil. In 1919 the Scotts moved to Greenwich Village where Evelyn became one of the bright young stars of literary bohemianism with her first collection of poems, Precipitation (1920), and her first novel, The Narrow House (1921). Darwinian, Freudian, and Nietzschean, Scott writes about the powers that lie beyond control, beneath consciousness.

The Narrow House focuses on a dysfunctional family that clings together, as intent on self-destruction as on self-preservation. No “clean and formal workmanship” is possible within Scott’s raw, confrontational art. Whatever civility exists within her community must be stripped away to expose the all-consuming powers of appetite and ego. Scott’s best work, Escapade (1923), is an experimental autobiography which captures Scott’s personal hell as she gives birth to her only child in a verdant, infested Eden. Scott writes about pain, physical and psychic, and she offers no assurance that community can offer protection. In 1927 her novel, Migrations, begins her shift from more concentrated, imagistic novels to more historical, southern novels, but her style remains experimental as exemplified by her stunning Civil War novel, The Wave (1929), a novel organized in vignettes similar to John Dos Passos’ Manhattan Transfer (1925). Scott established her reputation before Faulkner and aided him with her introductory essay on the soon-to-be-released The Sound and the Fury. She published a total of nineteen books, but even before her death in 1963, she had been nearly forgotten. Her opposition to the powerful leftist critics of the 1930s led her deeper and deeper into paranoia and oblivion. Although she agreed with the Agrarians that communism was not a viable solution to what ailed America, she was equally critical of what she perceived as the Agrarian tendency to envision a stable antebellum society as a model for a future society. In Background in Tennessee (1937), Scott argues that Tennessee never had time to establish a stable society before the Civil War and considers the southern aristocracy a cultural illusion. Scott looked at the world from T’other Mounting. Like Harris, she cut beneath what she saw as the artifice of culture. She believed in the power of the primeval, and her art would not adapt to cultural traditions and expectations. For Tennessee literature, Scott represents a minority position within the modernist period. With Nashville as its center and Ransom as its master, the Fugitive/Agrarian/New Criticism movements defined the nature of southern life and southern literature. The most accomplished writers of this group were marginal Tennesseans: Allen Tate and Robert Penn Warren, Kentuckians by birth, although both had “border backgrounds” and spent a number of years in Tennessee. Tate was born in 1899 in Winchester, Kentucky, and moved frequently during his childhood, including briefly to Nashville where he later returned to attend Vanderbilt. During the 1930s, he lived with his wife, Caroline Gordon, at Benfolly, their farm outside Clarksville which became a popular outpost of the Nashville-based Agrarians. Tate’s role is central to all three tiers (Fugitive/Agrarian/New Criticism). Among his best poems are “The Mediterranean,” “Aeneas at Washington,” and “Ode to the Confederate Dead.” As a poet Tate is similar to Ransom in that his most admired poems were written in his youth (before 1935), although he, like Ransom, continued to revise his poems through the second half of his life. Tate’s poems tend to be more self-consciously erudite, but, like Ransom’s best work, they are wonderfully controlled meditations that emphasize the degeneration of modern man from a lost heroic tradition. In “Mediterranean,” after imagining Aeneas’ ancient heroic quest, the conquest of the New World is described thus: “We’ve cracked the hemisphere with careless hand!” In “Aeneas at Washington,” the eternal Aeneas begins with his valor in leaving Troy but concludes with his New World vision: “stuck in the wet mire.” And in “Ode to the Confederate Dead” the impotent meditations of the modern man must occur outside the gate of the realm of the heroic Confederate dead. In his late years, Tate devoted more time to criticism and, like Ransom, promoted the literature he admired (Dante near the top of the list, Poe near the bottom), while also developing the New Critical approach to literary study, an approach that encouraged close examination of the text, an appreciation for literary devices and artistically achieved unity, and a respect for tradition without facile, superficial preoccupation with biographical and historical background.

Robert Penn Warren was befriended by Tate soon after Warren arrived at Vanderbilt. Warren, born in Guthrie, Kentucky, in 1905, was only seventeen at the time. As the youngest member of the Fugitive group, Warren quickly established himself as one of the best poets. Yet unlike the careers of Ransom and Tate, Warren is more likely to be remembered for his late-life poetry. Warren might best be seen as the John Dryden of his age. His total impact in literature is difficult to gauge because he is equally accomplished in poetry, fiction, and criticism. Typically, one now finds more emphasis on his poems published after 1950, including his long poems, Brothers to Dragon (1953) and Audubon: A Vision (1969). Some of his best poems were published after Warren’s seventieth birthday: “American Portrait: Old Style,” “Mortal Limit,” and “Doubleness in Time.” These poems drop the classical structure and more austere detachment of the Fugitive period. As a critic, Warren combined with Cleanth Brooks to write the influential New Critical anthologies that shaped America’s literary landscape after World War II. Yet Warren’s intellectual connection with the Fugitive/Agrarian/New Criticism movements was tenuous even in the earlier stages. His contribution to I’ll Take My Stand, “The Briar Patch,” called attention to racial injustice and was considered too progressive by Donald Davidson. In later years, Warren’s views on desegregation moved him yet further from Davidson’s conservative position.

Warren’s fiction typically portrays the Tennessee/Kentucky border area beginning with his first novel, Night Rider (1939), which portrays the area’s Black Patch War between tobacco farmers and tobacco companies. This rural area, as in his short story collection, Circus in the Attic (1948), draws upon the history of his home territory, essentially the triangle from Guthrie and Hopkinsville, Kentucky, to Clarksville, Tennessee. One of his best early novels, Gates of Heaven (1943), and his brilliant last novel, A Place to Come To (1977), use both rural Tennessee and Nashville. The novels are worthy of close comparison as Warren introduces a Dantesque vision of Nashville in both cases. Gates of Heaven investigates how a former college football hero, Jerry Calhoun, is released from his agrarian roots and corrupted by progressivism. The entrepreneur’s daughter, Sue Murdock, is an excellent portrayal of the 1920s new woman who is independent and brazenly aggressive on the surface but beneath the surface has been damaged by a loveless family. A Place to Come To offers a similarly powerful but damaged woman, Rozelle Hardcastle. The protagonist, Jediah Tewkberry, is like Jerry Calhoun in that the story involves his movement from an agrarian background to urbane sophistication. Again, Warren contemplates the dangers of what is lost by disassociation from one’s agrarian roots, but in this case one can see that Warren’s Agrarian principles have faded to the background. The later novel, like Warren’s late poetry, employs a more personal and picaresque approach to experience, one less inclined to read personal history according to the Agrarian paradigm. Warren’s affection for far less disciplined writers, like George Washington Harris and Theodore Dreiser, is apparent, and the treatment of explicitly sexual material is a deliberate affront to conventional good taste. Although Warren has consciously used Dante’s Inferno as inspiration in both texts, in A Place to Come To, he is equally inspired by Yeats’ “Crazy Jane Talks with the Bishop” and has, as in his late poetry, created a more complex tension between art/life as conscious design and art/life as uncontrollable, inexplicable engagement. A Place to Come To deserves to be ranked with Warren’s finest novels, All the King’s Men (1946) and World Enough and Time (1950).

Two accomplished Tennessee fiction writers who are closely connected with Ransom, Tate, and Warren are Andrew Lytle and Caroline Gordon. Both are passionately Agrarian, and both are consummate craftsmen. Lytle was born in Murfreesboro in 1902 and one of his earliest publications is his contribution in I’ll Take My Stand, “The Hind Tit.” He was a teacher of writing through much of his life (U. of Iowa, U. of Florida) and is as well known for his editorship with the Sewanee Review as for his novels; however, his novels are impressive achievements, particularly the short novel, A Name for Evil (1947) and his final, experimental novel, The Velvet Horn (1957). A Name for Evil is a reminder of the profound influence of Henry James on the Agrarian writers. The novel, a psychological gothic thriller much like The Turn of the Screw, is a nightmarish contemplation of the force that land has over humans. The Agrarian concept of the return to the ancestral land is here investigated in terms of the dark stain upon the human that prevents a return to pastoral tranquility. A disturbing illustration of the conservative Agrarian’s difficulty in dealing with race is apparent in Lytle’s early story, “Mr. McGregor.” In this story of an antebellum plantation, the planter kills a slave when the slave attempts to avenge the whipping that Mr. McGregor has given the slave’s wife. Lytle’s focus on the complex dynamics of Mr. and Mrs. McGregor unjustifiably diverts attention from the brutal reality of slavery.

Caroline Gordon, like Lytle, is a conservative Agrarian who is also well known for her teaching as well as her writing. Gordon was born in Todd County, Kentucky, less than a mile from the Tennessee border. As a child she moved to Clarksville where she was educated in her father’s classical school. Gordon was far more prolific than Lytle, publishing nine novels and two collections of short stories before her death in 1981. Like Lytle, Gordon is never lacking in proficiency; she is essentially a writer’s writer. As exemplified by her first novel, Penhally (1931), her fiction often uses her Meriwether relatives who settled along the Kentucky/Tennessee border around 1800. Life in the fictionalized Clarkville is associated with the decay of Agrarian ideals. Her best novel may be Aleck Maury, Sportsman, her collaboration with her father. None Shall Look Back (1937) is often ranked among the best Civil War novels, The Garden of Adonis (1937) is her perceptive Agrarian response to the Depression, and The Women on the Porch (1944), a dark contemplation of love relationships inspired by her tumultuous marriage with Tate, is her most underrated novel. After this novel, Gordon’s fiction is deeply influenced by her conversion to Catholicism. The most successful of the later novels is The Strange Children (1951) which fictionalizes her life at Benfolly during the 1930s. As impressive as Gordon is as a novelist, her greatest accomplishments may be her short stories. Like her novels, her stories are always technically refined (Gordon would become Flannery O’Connor’s technical adviser). Among her best stories are “The Petrified Woman,” “Old Red,” and “The Presence.” An oddity of Tennessee literature is that the small city of Clarksville produced two important writers, Gordon and Scott, at approximately the same time and that these women looked at Tennessee from such sharply contrasting perspectives. Scott is the voice of T’other Mounting, essentially countercultural; Gordon is the voice of Old Rocky-Top, essentially reaffirming the importance of traditional art and culture.

(from The Companion to Southern Literature, Eds. Joseph M. Flora and Lucinda H. Mackethan. LSU, Baton Rouge: 2002.)