1.

Stitch

A thimble on my middle finger, to press the needle through, left hand on the cloth, laid flat on the table, to keep it steady. The thread is doubled, and harder to work with two layers of knit. I’m free handing the design because I hate to follow patterns, but I look at a picture to get a sense of how it could look. A flower with wide petals. I stitch around each petal—down, up, pulling apart the threads and tightening the one that’s caught up. This is patient work, and I am not always patient. People keep telling me to slow down, not to push so hard—look at all you’ve done, they say. They don’t know, though, that I lost twenty-two years, and now I’m playing catch up. My back gets sore, hunched over the table. I’m keeping the fabric flat so the flowers don’t pucker and bunch. When I’ve stitched around a petal and knotted it off, then I cut off the top layer of cloth, and reveal the underlying blue, paler than the top. This is reverse appliqué. Cut away the top layer to make the picture. Reveal, slowly, what’s beneath. You’ll never get to see it all, just what’s stitched and cut away. I have certain needles that I like best—the thinnest shank, and a wider eye for threading. If I’m not listening to a story as I sew, or music, then I’m in silence, and I can hear the thread going through the fabric, a sssssshhing sound like a whisper. A pause before I dip back in. Shhhhhhh. My hands on soft cloth, like my hands on a horse’s neck, where there is only breath and touch, into calm.

I came into sewing because words couldn’t say anymore. I needed the tactile, the slide of fabric underneath my hands, steady sound of the sewing machine, something made— complete—in the end. An object to hold, colors to lift.

Sewing became precision of expression.

Before I lost words, I wrote a series of things in Johnson, Vermont: the words were stranger shorter pieces than what I’d written before, and later, after I made the images, the words wanted to be paired with the images. So they became The Experiments. I was with visual artists during the residency in Vermont, and they talked about their work and could do things in their work that I loved—they were raucous and brave, louder than the writers in every way—smoking and drinking all night, slugging to their studios to get their hands into colors, to collage and paint and draw, to perform in black leather outfits with chains, to use saws and hammers and tear and listen to music as they worked (while the writer’s building was a hush, and there were complaints if anyone could hear anyone else from room to room).

2.

House with Copper Gables

Containment was the thing, a holding inside, and then there came the building where others had been housed, people from the past, whose names floated up like old heroes, strangers with bright, tassled flags.

At the bottom of the field, there was a great mansion, copper topped eaves, and an angular skylight that rose from the center of the roof, between four chimneys. Someone must have lived there—this place designed to feel like a college campus, settle in as if it’s home. In the olden days, Sylvia Plath, Robert Lowell brought their clothes and books and things to keep them happy; not a room but an apartment, a whole suite. They stayed for years; it was not just a passing point.

Linoleum floors, tunnels underground, a door that says, “Danger, High Voltage,” rough concrete floor underfoot, and upstairs the winding staircase, shining woodwork along the walls, same as when those others were here, spindled bars to keep the people from jumping to their death—I took all of this, walked through.

It isn’t like they say. There’s all this laughter, too: a girl with a knife, a man who prayed too much, a girl blowing bubbles. One of them brought me a balloon that said, “Welcome!” for my birthday. She had stolen it from a nearby fence, and I was honored.

For so long, there was a lake inside me, and then it drained. When I look in, it isn’t there. I go back and sit in the hallways. People walk by, people I know, floors creak, we say hello, chat and smile—all of it familiar, normal, a strange old kind of home, where I got free.

3.

If I’d lived a very long time ago (1834)

they’d have stuck a post into my brain

through my eye (very common), or cut

a part of it out, as a cure. And I, or

Vegetable-Me, would live on.

Weeks after, M and I walked through the woods in another state,

landed on the grounds of a hospital—

you could tell by the way it looked, it was mental

for the crazies

(plus, bars on the windows, the buildings meant to look like houses,

and in such a bucolic setting! Send them here! Lovely respite!

Shock therapy, lobotomy, tie them down, talk it through and through and through)

there was a pond—

we walked around, under yellow birch trees, then up the hill to the hospital,

M saying, The post, right through your eye—Stop, I said—and then we were laughing, that this is where we’d land, when we’d—ha! No one knew! —

(Shhh!)

—just left

—/ Frontal lobe,

rational thinking

This is your lizard brain, where instinct lives. It has been trained by millions of years, outsmarting sabre toothed tigers, hunting woolly mammoths, avoiding the fire (burn).

Everyone has a lizard brain.

It has kept you alive. It is why you run when you are startled, why you avoid what you’ve learned will hurt. But in some people, the lizard brain believes it is still on the lookout for the sabre-toothed tiger, that every cricket chirps a warning, that any thud means run.

In these people, the lizard brain has to be retrained. All the paths in the brain have to be retrained. And this is called exposure.

4.

By the Yard

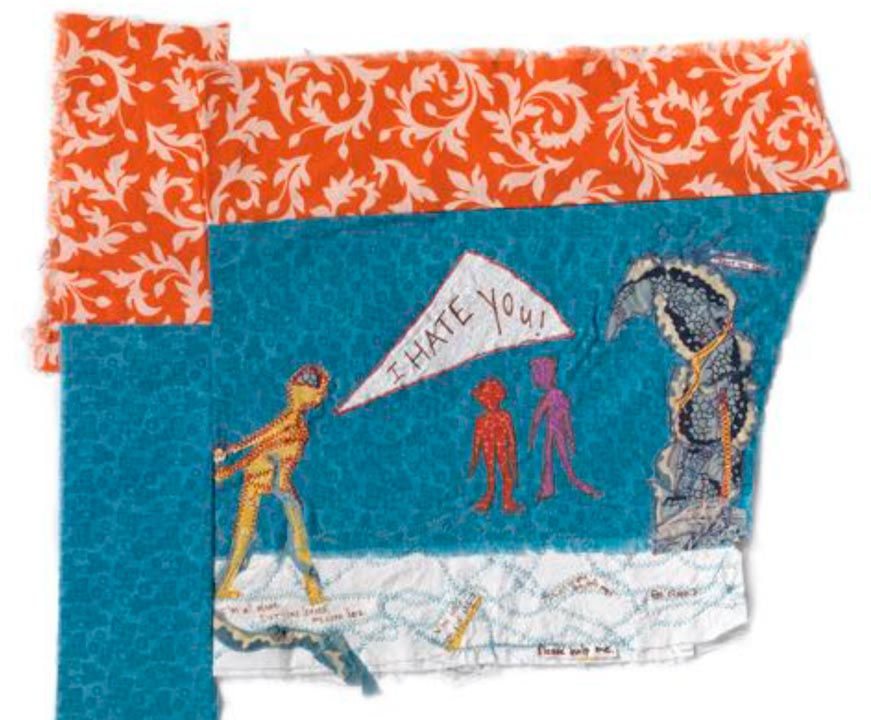

Salvation is the sound of a sewing machine making picture after picture, desperate for any small respite. Red fabric sliding, layers of blue and orange curliques, prettiest red roses saved for the center of bodies, person after person walking forward, hands on their heads, screaming for some answer: I hate you! to the people who seemed not to help. There was only fabric that could save, or walking through the sculpture park, up and down the hills, past Jim Dine’s “Three Lines” and “Two Big Black Hearts.” Touch fingerprints in the clay, wonder how he chose hammers and faces and ropes. All that delicacy in the hulk of a form, woods beyond, the smell of pine, other people in the park, walking. Murmuring about what they did and did not like. Walk to the hanging wind chimes, grab a stick from the cup, and run the stick along the chimes, just to hear that sound, to remember play, to make some noise that echoes.

Sharp. [Exposure.]

She plays the piano even though she is afraid, imperfect—if she hits an off key, everyone will die. Over and over, one sonata after another, compositions she used to love. She weeps, hates this, hates it. It is an old piano and out of tune, donated, says the old man, in the eighties. He laughs when he talks about eating food out of the toilet, says, now that’s extreme. Off the seat, sure, but not from the water he is jolly. southern accent. I leave his office and walk outside, closer to relief this summer than I’ve ever been. Twenty years and now’s the time to plow forward. The windows are open, heat wave and the air conditioner’s broken. Sundress days. A little breeze, and the sun comes through the trees. I can hear her playing right through to the end, a sharp where a flat should be, and she goes on.

5.

The lizard brain will listen to repetition and lived experience. That’s what you teach the lizard brain with Exposure.

The lizard brain won’t listen to you if you try to explain to it; it’s a lizard, for crying-out loud! Treat it like you’d treat a dog. Sit! Good, dog. Lie down! Good, dog. Ignore the dog when it begs or jumps up on you—that’s how it will learn. Even if it whines and cries and looks so miserable and sad—ignore that dog. Don’t give it the bad thing it wants.

The bad thing is the compulsion.

Take away the compulsion, the obsession shrinks and shrivels. That dog will eventually lie down and be good.

“People with OCD always know that their thoughts are a product of their own mind. If you believe that other people’s voices are speaking to you or controlling you, then you should see a qualified psychiatrist or psychologist as soon as possible to get help for your problem.

Happily, the vast majority of people with OCD do not truly believe in their obsessions, except when they are trapped in an OCD loop of obsessions and compulsions and are feeling anxious; this is common.” —Baer

Mine didn’t look like anyone else’s. If you had said to me, OCD, I’d have said, hand washing, counting, not stepping on the cracks, stereotypical movies like Something’s Gotta Give. I never knew to look under that name for something that was like what I felt. Never, never, not for twenty-two years. That’s one of the reasons I never knew. And it wasn’t until I got some of the other things, things that did look like everyone else’s—washing my hands over and over because maybe I’d gotten rabies from the lost dog I’d tried to help—that I looked things up online, and then I saw all the other symptoms, too, and the blocks came tumbling into my lap. And six months later, I knew. Diagnosis. Spoken, stripped bare, done—my whole life recast with this in mind now. Why didn’t I know sooner? Why didn’t anyone tell me, or try to help? Those therapists I saw before, who made it worse—I was angry at them, and at everything I’d missed. It wasn’t me that was a monster but that I had a monstrous disorder. Which took away all those years, and my imagination for a future.

6.

Trigger.

(What sounds like Pooh’s friend?)

No touching. We are not supposed to trigger each other but we do, once we’re friends and joking and better than when we got here. Everyone comes in with agony in their eyes. Then—if they stay—there’s an easing, even laughter, eventually. Lunchtime salads and pasta—too much pasta!—the running joke. Jokes of contamination, of the number sixty-six, intrusive thoughts (murders and stabbing and theft, oh my!), losing something we very much need, objects being crooked, something just not right—clenching stomach, pressing fear. But here, this is the stopping point. Resist the urge. Turn off the faucet. Let the hands remain filthy. imagine the worst—all those deaths, yes, might happen. Sit with the uncertainty!, we laugh, our mantra. Oh. How it hurts. We know it is all ridiculous, irrational, we know, but we cannot—quite—believe until we try, over and over, to make ourselves sick with touching, to think the worst, hope for the worst. Drive into the fear. Welcome these sick moments. You have to be brave, to very much want this cure.

7.

Years will go by, and you’ll unroll the scroll of accomplishments you stitched at the hospital during group meetings. You’ll remember laughing on the couch with the man who couldn’t walk through doorways, who would “get stuck,” rocking back and forth in the middle of the room. Watching him paralyzed was watching yourself—wanting to move but unable to move, the loop that repeats. But by the end, you both got better, and moved to the white house down by the road, where one night, in a cabin fever daze and the delirium of relief, you threw leftover lettuce onto the lawn for the rabbits (though there was plenty of grass) and then waited for them to appear and graze, as they did every night. You laughed together about losing your minds in a mental hospital, about how the rabbits didn’t even eat the lettuce. You laughed about each of your obsessions, about the absurdity of it now, in retrospect—and how good it felt to laugh, at last, at what had kept you captive.

In the dusk, the woman who couldn’t walk through grass because she feared lyme disease from ticks strolled towards the house just after dusk. We watched her come through the orchard and across the lawn, moving with ease; weeks before, she wouldn’t have been able to bear the grass against her ankles.

Some of the people we’d known here had left, unable to complete the program. They went home angry, or disappointed, or they were kicked out for doing something inappropriate—sleeping with other patients, hollering and chasing someone down a hall. Or they couldn’t afford it anymore. Their insurance wouldn’t cover the $700-a-day bill and their families had drained their pooled bank accounts, and they had to leave with whatever they’d done so far. When they left, they left with grief, and we all knew they might or might not come back, might or might not live. There were plenty of stories of people who had died. A man was stuck in a bathroom in a fire. Last year, you lost a friend; he killed himself.

But the lucky ones, who were able to stay, they left different. Their whole demeanor changed. They could look you in the eye, could tell their own stories without crying, think with hope for their futures.

You and that man would go out for Starbucks with the high school girl who feared stabbing other people; you would walk into the shop and no one would look at you askance. You would realize you’d never lived without this secret before, not since you were ten, and now you could. You would feel, for awhile, in love with the whole world, with that burning orange fall tree that struck you one day as you drove down Main Street and cried, for the first time, from happiness.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Rachel May is a writer and self-taught fiber artist. She’s the author of Stitches in Time: Family and Slavery in Mercantile America (forthcoming, Pegasus 2017), Quilting with a Modern Slant (Storey/Workman) a Library Journal and Amazon Best Book of 2014, and two collections of fiction, The Benedictines, a novel (Braddock Avenue Books 2015), and The Experiments: A Legend in Pictures & Words (Dusie Press 2015). She illustrated, in appliqued and embroidered images, the paired novellas Women Born With Fur & Out from the Pleiades (Jaded Ibis Press 2014). She’s been awarded residencies from The Millay Colony and The Vermont Studio Center, and her writing has appeared in The Los Angeles Review of Books, Michigan Quarterly Review, Indiana Review, Meridian, Memoir(and), The Journal, Cream City Review, and other journals.