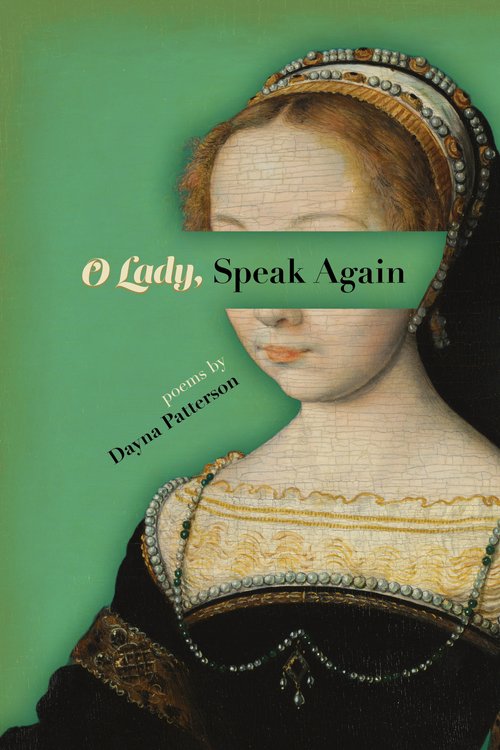

In her collection of poems, O Lady, Speak Again, Patterson gives new voice to Shakespeare’s canon of female characters, while positioning them against the backdrop of the speaker’s own stifling upbringing within the patriarchal Mormon church, without a mother to guide her.

In a time of sleek, short, synthesized poems, Dayna Patterson reminds us of the joy of words. Words on words on words. She proclaims the power of our words and the “madcap mouthmagic” they make. These poems delight in their own wild sounds: “your lintel, liminal goddess,” “a mouth of moan.” Alliteration and repetition and internal rhyme stitching together otherwise dissonant ideas. Patterson explores the way that the written and spoken word can connect us, even across time.

In these poems Patterson finds a way to “wardrobe the heart and clone / each scar.” Themes of grief and sisterly love abound as she catalogues the ways in which so many women’s hearts have been broken in the same places. Famous leading ladies like Lady Macbeth and Juliet are poised as mirror images of the speaker in her self-portrait poems as they all suffer at the hands of men, and buck at societies that refuse to let them make their own choices.

She tries these characters on like auditioning for different roles or grabbing costumes from a rack. She sees her own pain and love and loss in each character, fitting their names on for size, but imparting something of herself as well. As she tells these characters’ stories, she also reveals bit by bit her own story of patriarchy and the suffocating voice of the church in her ears. Between herself and these female characters, her poems cast a spell, binding them together as a “coven of sisters,” but these characters also serve another purpose. She seeks in the familiar figures, not just a shared understanding, but a new ending.

Patterson frames many of these poems as scenes in a new play, or, more accurately, rewrites of an old one, such as in the poem “In this version” where “Romeo doesn’t drink the apothecary’s poison, / and Juliet awakens in his arms.” Patterson’s pen is pointed to the past, but these are Shakespeare’s characters as we’ve never seen them. She doesn’t simply mourn Ophelia or Desdemona, she throws back the curtains, slams on the stage lights, and tries to write them out, into a better future, a brighter ending, for them, and for her.

This collection could easily descend into tedium or pretention as it trots out old characters from ancient, overstudied plays, but it never does, because these poems don’t stem from a passing interest in Shakespeare or history. These poems feel vital. Patterson is not just reimagining the lives of Shakespearean women, she is reimagining the speaker’s life as well into one where the home she grew up in was safe and supportive, into a life where her mother lived, and her “mother’s face [became] familiar as sun on her skin.”

As in Shakespeare’s most famous plays, ghosts roam the halls of these poems and render centuries-old stories, tenderly personal again. The ghosts of cruel fathers and unknown mothers pass through these pages, visceral and tangible as any other character Patterson paints. In her self-portrait poems, they fog up the mirror, and complicate her character studies. The speaker’s past haunts this book, heavy and potent as any Shakespearian play. Through vulnerability and immense empathy, Patterson is able to weaponize personal history as a tool to crack open these old characters. She gives them voice and then sits down and acts as congregation, listening to their stories/sermons/songs as though they are her own sisters.

Above all this collection is a triumph in love. Love for sisters and mothers and daughters. Love for generations of women carving life out of a narrow box. Love for history and the past that forges us but does not define us. Queer love hard won from a society that would see its flame squashed to cinders. Love of language, which cleaves and brings together. Love of those who came before, and the words they brought, and how those words sing like starlight from hundreds of years away, even now. And love for the self. More than anything, the speaker honors the love she has found for herself, and all the women she contains.