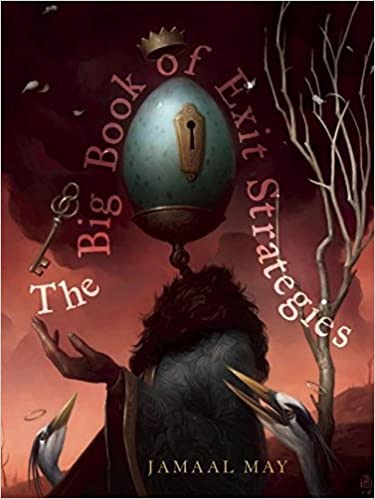

Jamaal May’s second collection, The Big Book of Exit Strategies, continues to meditate on the landscapes and figures of Detroit, but where his debut collection left off, these poems leap forward—away from the machinations of industry and humanity that powered Hum and into a kind of magical wilderness, where memories and reflections of urban place blossom into the mystical and nostalgic, confounding the kind of imagery and tropes readers might expect. The poems in The Big Book of Exit Strategies are thus both a departure and a kind of growth from the scenes laid down in Hum. Readers will find themselves warmed by the enormous amount of love in these poems—love for place and for overlooked miracles—and simultaneously engaged by May’s edgy syntax and mash-up conceits.

The book reads as a kind of love letter to hidden treasures and endearing battle scars, and the poems craftily deconstruct the ways that discourse reshapes or overlooks gorgeous and transformative moments, as in “There Are Birds Here,” in which the speaker gives a number of corrections regarding the landscape of Detroit:

No,

I don’t mean the bread is torn like cotton,

I said confetti, and no

not the confetti

a tank can make out of a building.

I mean the confetti

a boy can’t stop smiling about… (2)

The speaker’s insistence on wonder, on the state of awe as a pure thing, juxtaposes sharply with the insinuations of “they”—the misreaders—who won’t stop saying “how ruined the lovely / children must be / in your birdless city” (3).

The Big Book is also full of transformations—both worldly and otherworldly. “Ode to the White-Line-Swallowing-Horizon” does this nicely:

Apologies to the grown man growing out

of a splintering boy’s body, all apologies due

to the splinters. Little ones,

you should’ve been a part of something whole. (4)

Here, like in the collection’s opening poem, “Ask Where I’ve Been,” it is the speaker who is transformed. In other places, we see characters and creatures metamorphose before our eyes, as in “From the Big Book of Exit Strategies”:

Fig. 57: A fisherman pulls his nets from the waters

and finds a version of himself twisted in them,

gasping for air that is all around him

but inaccessible because some god

put gills where there should have been lungs… (16)

It is easy to become lost in the gorgeous dreamland that May lays out, but these poems also have bite. “From the Big Book of Exit Strategies” weaves its surreal narrative around the scar left from a bullet entering and leaving a human body, a portal through which we are led to contemplate a folkloric series of illustrations found in the imagined book. These moments, along with a woodland god and a zombie Jesus, give the collection a transdimensional quality, as if we have stepped into a liminal space to witness something rare and secret and also somehow familiar.

Conversations seem to rattle across this collection. Again and again, we find poems that reflect an imagined dialogue or supplant a known narrative. Poems build on and challenge existing discourse, and even the more straightforward poems in the collection are full of referenced speech acts. “Mouth” displays the kind of meditation on dichotomy and discourse that exemplifies much of May’s work in this vein. The poem is in two sections, both sestets: the first describing the addressee’s mouth, wired shut after a fight, and the second describing the speaker’s:

Mine is becoming a trap for what I don’t say. What is bitter

choked down but no sweeter spit up, all copper

and slime, chipped from a rotted tooth, is spit,

blood, blood and spit. (40)

May’s use of repetition has been called percussive in the past, and if that’s so, then these new poems are cacophonous to various effect—sometimes lending a sense of urgency or to illustrate disagreement, other times to lull the reader into a sort of trance with its mythic, almost fairytale-like syntax, and more often than not, for the kind of exploration of dichotomy that characterizes his work, as in “A Brief History of Hostility”:

In the beginning

there was the war.

The war said let there be war

and there was war.

The war said let there be peace

and there was war. (23)

Elsewhere, May’s twisting syntax seems to favor conditional structures and negations—grammatical approaches that pivot and surprise. These moves work nicely against his most frequent approach to the line break as annotative and the stanza as a central unit of meaning in poems.

If there are moments in The Big Book that seem less than careful, they are few and far between. Some might find that poems like “Unsigned Letter to a Human in the 21st Century” lean a little too much on conceit, sacrificing pleasure for the ear in exchange for interesting ideas (106). The collection’s self-reflexive gestures will either be met with a chuckle or mild annoyance. May refers to poets and poetry, including his own, frequently in his work, and it doesn’t always feel artful or necessary.

Those who enjoyed his chapbook, The Whetting of Teeth, will be pleased to find new additions to his phobia poems present in this new collection as well as the sonnets, which reappear with some interesting revisions to form. Mostly, readers will be in awe of May’s inventive conceits and luscious language, especially in poems like “The Spirit Names of Stolen Books”:

I call your copy of Song, Ruby-Mouth, and last night

I sat in the lamplight with Clean-Tooth,

whom you know as Ariel, and the smile of the snow

she mentions was nearly toothless by then… (85)

It is this kind of inventiveness that makes May’s work such a sublime pleasure to read. There are many, many moments of genius and music packed into this collection, and readers will be excited about the ways it expands and builds upon his previous work.