One of the more disturbing aspects of French filmmaker Claude Lanzmann’s masterful 9 ½ hour Holocaust documentary, Shoah, is the beauty his camera often captures. A river turns gold beneath a late afternoon sky, and a few miles away, wildflowers sway among the ruins of concentration camps. When a bird calls from the woods, you begin to understand that the spring sun sometimes warmed the necks of those who arrived at Auschwitz and Buchenwald. On the types of days when we eagerly open our windows, the crematoriums’ chimneys sent plumes of black smoke into a clear sky.

Suffering and death aren’t confined to the gray months of winter. In 1986, the Eastern European country of Belarus, then a member of the Soviet Union, enjoyed a mild spring, that sent people, in April and early May, to sunbathe and swim in the country’s rivers and lakes. These vacations coincided with an emergency at the nearby Chernobyl Nuclear Power Station, which had caught on fire after a series of explosions. The fire would result in the greatest nuclear disaster in history, and as the former director of the Institute for Nuclear Energy at the Belarusian Academy of Sciences said to the journalist Svetlana Alexievich, the people didn’t “know that for several weeks now they’ve been swimming and tanning underneath a nuclear cloud.”

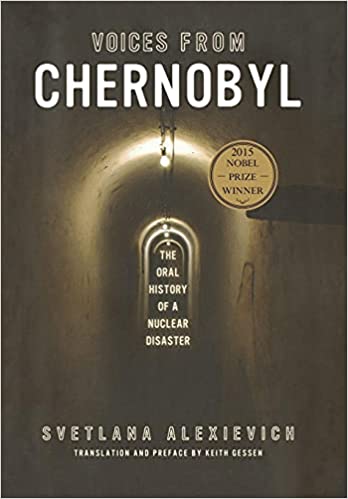

Alexievich, like Lanzmann, gives us a true picture of the disaster in her book, Voices from Chernobyl: The Oral History of a Nuclear Disaster, by juxtaposing its horrors with the beauty that surrounded it. On April 27, the burning reactor gave off a “bright-crimson glow” that sent people in the nearby town of Pripyat onto their balconies. “They stood in the black dust, talking, breathing, wondering at it,” one of the town’s evacuees recalled for Alexievich. “People came from all around on their cars and their bikes to have a look. We didn’t know that death could be so beautiful.”

Alexievich spent three years collecting interviews for the book, which first appeared in Russia in 1997. An English translation came out in 2005, but when the author was awarded the 2015 Nobel Prize in Literature, it created a renewed interest in her work.

This powerful book, however, does not showcase Alexievich’s gifts as a writer. The only place where the reader discovers her voice—except for brief asides throughout the text—is a short, two-page epilogue in the back. In that sense, she is more like the filmmaker Lanzmann, who uses no archival footage or staged recreations in his mammoth documentary. Instead, he lets the participants—the victims, the witnesses, the concentration camp guards—tell their stories. Alexievich’s book is a collection of monologues she collected from the survivors, and she has expertly arranged them to present a full, emotionally compelling mosaic of the one of the great tragedies of the twentieth century.

The tragedy of Chernobyl will continue to haunt the land and the people who lived there. That patch of earth will remain contaminated for tens of thousands of years. The human farmers and soldiers and factory workers who called that area home will see their family lines either come to an end, or face the dangers of procreation. A historian comments on how, in 1993 alone, Belarus saw 200,000 abortions, and the specter of giving birth haunts the book. A resident of the village of Khoyniki recalls how her daughter told her, “Mom, if I give birth to a damaged child, I’m still going to love him.”

And yet, every year the spring sun returns to warm the necks of this doomed population.