When the unnamed narrator of Sara Majka’s short story, “Four Hills,” meets an attractive, older man, she immediately checks his hands.

“He had a ring, and so I told myself, There, now you know, and I felt the calm settling of disappointment as it joined the tide of all the other disappointments, the soft, great ocean of disappointment that comes from living among millions of others who also want things, sometimes the things that you want.”

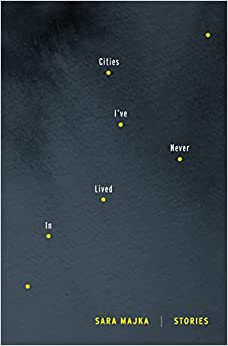

This quiet, unrequited yearning is the bruised heart that pulses through Majka’s hypnotic collection of stories, Cities I’ve Never Lived In. The characters in these fourteen stories, set mostly in a desolate, coastal Maine “where the sun was so slant and spare that by January you felt it could disappear,” suffer from deep longings that threaten to overwhelm them. These individuals reflect the region’s sparse landscape, with Majka pushing aside specifics—hair color, job titles, names—leaving only the raw emotion of an encounter. The narrator in “Boy with Finch” avoids all superficial details when remembering a long-ago incident with her mother.

“Once, when I was a child, she took me to a mental health clinic. She knew one of the doctors and wanted me examined. Afterward, the friend let her walk me through a set of doors and down a hallway. The hallway ended at a cube, with windows and children in bright clothing. There were many children, some drawing, some sitting against the wall with dark circles under their eyes. Some crying. My mother behind me, hands on my shoulders, keeping me there, until at last she turned me and we went back.”

Majka’s bare prose causes theses stories to feel more like dreams, so that when you put the book aside, the details fade, but the feelings of loss and anguish remain. Instead of memories of characters and events, the reader recalls Majka’s simple, beautiful sentences, as when the lonely narrator of “Reveron’s Dolls” talks about clamming.

“I know a little about the lives of clams, though I’m left with the idea that they drift, that the tide raises them and they skirt along until being brought down.”

Some readers might liken Majka’s style to Raymond Carver or Ann Beattie, but the comparison would be inaccurate. Instead of presenting life in a deadpan manner, Majka’s stories conjure a sort of milky fog that obscures all but the heartache of yearning and loss. In “Strangers”—the strongest story in the collection—this emotion calls out like a foghorn when the grandfather looks at his abandoned grandsons.

“He liked to look over while he drove—at the way the wind went through their hair, at the broken-down toughness of the truck—but he never said anything about it. What they might have thought of him, though they probably didn’t think much about him, probably just thought of him as a permanent thing.”

After reading this beautiful collection, astute readers might think briefly of Richard Ford’s famous story, “Great Falls,” because the first line of that tale—“This is not a happy story. I warn you,”—would serve as an appropriate epigraph for Majka’s stories. These are not happy stories, but no warning is needed. Majka’s collection needs to be felt, helping readers avoid the malaise that is overtaking so many of her characters.